How to Write a Good SRS (Software Requirements Specification): A Complete Guide with Examples

The Software Requirements Specification (SRS) is a critical document that can make or break an upcoming software project when it is first kicked off.

While it’s not the most glamorous artifact, it is the one that ensures that all project managers, developers, testers, and clients stay on the same page with regard to what should be built and how it should function.

| Key Takeaways: |

|---|

|

Understanding the SRS Document

A complete description of the software system that is being developed is called an SRS document. It clearly defines the system’s non-functional (how the software should behave in different scenarios) and functional (what the software should do) requirements.

It usually behaves as the single source of truth that ensures that everyone has the same understanding of the product. This is even before the first line of code is written; it can be considered a contract between the development team and the business.

Why You Need a Good SRS

An efficient SRS helps to reduce the gap between technical implementation and user expectations. In the absence of it, you may experience expensive scope creep, incessant revisions, and misunderstandings. A well-written SRS should have:

- Improve traceability throughout the software development lifecycle (SDLC).

- Reduce misunderstandings during requirements gathering.

- Works as a guide for software design and testing.

- Defines a solid basis for upcoming improvements and upkeep.

To put it in simpler terms, an SRS is the basis of expert project documentation because it ensures that the final product is built as promised.

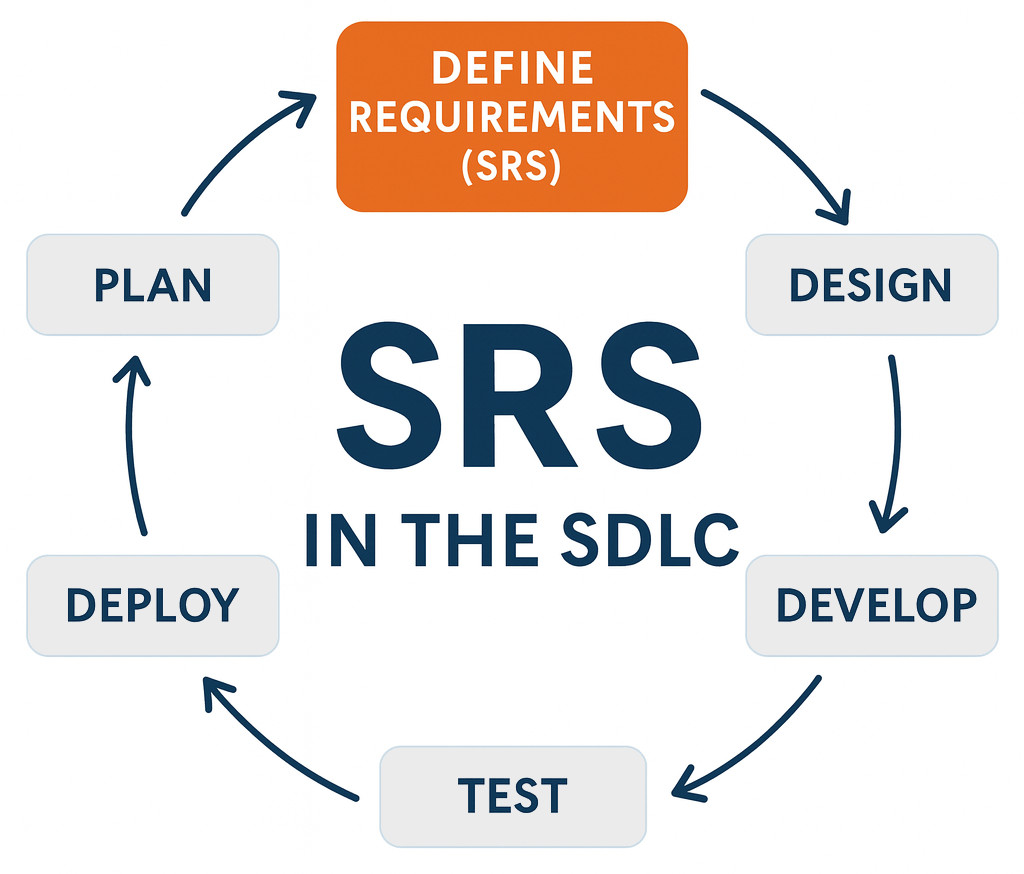

The Role of the SRS in the Software Development Lifecycle

- In order to understand what the system must accomplish, the team interacts with users, clients, and business analysts during requirements collection.

- Following the collection of those insights, they are collected in a structured and testable format in the SRS document.

- The SRS is then used as input by the software design document (SDD) to understand how those requirements will be carried out.

- Later stages, like coding, testing, deployment, and maintenance, all make reference to the SRS to ensure accuracy and compliance.

Ignoring or underestimating the SRS phase is as risky, expensive, and chaotic as building a structure without blueprints.

Preparing to Write an SRS

You need a clear vision before you type even a single word. Gathering requirements thoroughly is the first step in building a strong SRS.

Compile and Analyze the Needs

- What issue are we trying to solve?

- Who is going to use the system?

- What are their main responsibilities?

- Do we need to integrate with any existing tools, limitations, or technologies?

The objective of this stage is to identify business rules, dependencies, risks, and both functional and non-functional needs.

Define the Purpose and Scope

Clearly establish the need for the software’s development and its goals. The scope defines the limits of what is and is not included.

Identify your Audience

- Business stakeholders who must validate goal alignment.

- Developers, who convert specifications into code.

- Validation criteria are built by testers.

- Project managers, who keep tabs on developments and outputs.

Write in an understandable, simple, and accessible style.

Structure of an SRS Document

An SRS template is used by the majority of successful projects to guarantee consistency in all documentation.

Below is a tried and tested structure that you can customize to your needs:

Introduction

- Purpose: The goal of this document.

- Scope: A short description of the system’s parameters.

- Intended Audience: The target audience for the document.

- Definitions and Acronyms: Clearly define domain-specific terms

An efficient introduction sets the expectations for the remainder of the SRS and prevents confusion in later stages.

Overall Description

- Product perspective: Is it an update, a stand-alone app, or a component of a bigger system?

- User attributes: Who will make use of it? What capabilities or restrictions do they have?

- Assumptions and Dependencies: Third-party integrations, external systems, or restrictions that could have an impact on the final product.

- Operating Environment: Hardware, OS, and network requirements.

Before diving into specific requirements, this helps stakeholders understand the context.

Functional Requirements

Functional requirements outline the accurate functions, actions, or features that the system must have.

Every functional requirement should be precise, measurable, and unambiguous.

- “Users will be able to access the system by giving their email address and password.”

- “The data must be validated before being saved when a user submits a form.”

Organize these as per the user type, feature, or module. For ease of reference in later documents like test cases or traceability matrices, each should have a unique identifier (FR-1, FR-2).

Remember that behavior, not implementation, is captured by functional requirements. Let the software design document handle the how.

Non-Functional Requirements

Non-functional requirements explain how the software works, whereas functional requirements define what the software does. They are often referred to as quality attributes.

-

Performance: Scalability, throughput, or response time.“Up to 10,000 requests may be processed simultaneously by the system, with a maximum response time of two seconds.”

- Security: Data protection, authorization, and authentication.

- Usability: Consistency in the use of the interface, responsiveness, and accessibility.

- Reliability: Expectations for uptime or fault tolerance.

- Maintainability: The ease of updating or scaling the system.

- Portability: The capacity to work across different browsers or platforms.

Non-functional requirements are important because they impact decisions about infrastructure, architecture, and design. Do not treat them like inferior second-class citizens.

External Interface Requirements

- User interfaces, including mobile, web designs, and desktop.

- Interfaces for software (APIs, libraries, integrations).

- Hardware interfaces (peripherals, sensors, and devices).

- Interfaces for communication (data exchange formats, protocols).

- Include mock-ups or diagrams if they help illustrate the flow.

Other Requirements

- Legal or regulatory requirements (such as GDPR compliance).

- Internationalization and localization (multilingual support).

- Needs for analytics or reporting.

- Business regulations that must never change.

Appendices and Supporting Material

- Definition: Give definitions for all critical terms.

- Use Examples or Schematics: Workflows should be visualized.

- Traceability Matrix: Map design or test cases to requirements.

- Revision History: Monitor how the document has altered over time.

How to Write an SRS: Step-by-Step

After discussing the structure, let us understand how to actually write your SRS.

Step 1: Start with a Template

Use a uniform SRS template to accelerate the process and ensure you don’t ignore any important parts. Change it to fit your project; small teams may merge some sections, whereas larger projects may add more information.

Step 2: Define Purpose and Audience

Start the document by concisely outlining the objectives of the software and the people who will use it. This makes everyone’s intentions clear.

Step 3: Explain the System Background

Offer an overview of the software’s integration with existing dependencies, systems, and business processes. Identify which external parts or APIs your system needs to connect to.

Step 4: Capture Functional Requirements

List out all required functions. Make use of precise wording (“shall” statements), unique numbering, and consistent formatting.

Step 5: Capture Non-Functional Requirements

Convert stakeholder expectations into quantifiable benchmarks. Write “system shall display search results in less than 2 seconds” in place of “system should be fast.”

Step 6: Review for Completeness and Consistency

Ensure the document is reviewed by multiple people, especially stakeholders with technical and business backgrounds. Every prerequisite should be: essential, feasible, consistent, testable, and traceable.

Step 7: Baseline and Version Control

Baseline the SRS and freeze it as the official version for development after the team provides its approval. To keep track of updates during the project, use versioning tools or change logs.

Step 8: Maintain the SRS Throughout Development

An SRS is an ongoing document. Update the project to reflect authorized changes as it develops. This avoids misunderstandings during testing or maintenance and maintains relevant documentation.

SRS Best Practices

Writing an SRS involves both documentation and communication. To make your SRS professional and efficient, follow these best practices:

Write Clearly and Precisely

Your sentences should be short and straightforward. Every requirement ought to have a single meaning.

- Do not write “The application should load rapidly.”

- Instead, write “On a 4G connection, the app should load the home screen in less than 3 seconds.”

Clarity prevents misunderstandings and later, costly errors.

Maintain Consistency Across the Document

Ensure to use consistent numbering, formatting, and terminology. Use a single term or provide precise definitions if you use “users” in one section and “clients” in another.

Make Requirements Testable

A requirement isn’t good if a tester can’t validate if it has been completed. Requirements should always be expressed in quantifiable terms.

Ensure Traceability

Every requirement should lead to a test case and be related to a business goal. Later in the software development lifecycle, it is easier to evaluate the effects of changes when a traceability matrix is maintained.

Collaborate and Review Frequently

Collect feedback regularly rather than only at the end. Gaps that might go unnoticed by business stakeholders are often discovered during review sessions with developers and QA engineers.

Keep the SRS Maintainable

Leverage version numbers, group related features, and steer clear of redundant descriptions. A maintainable SRS saves time when you need to make changes in the middle of a project or years later during maintenance.

Focus on What, Not How

The SRS specifies what must be built, not how. Implementation specifics belong in the software design document, so avoid the temptation to include them.

Prioritize Requirements

Sort requirements into “must-have,” “should-have,” and “nice-to-have” categories. Setting priorities aids in effective scope and resource management, especially when deadlines are short.

Align With Agile or Waterfall Methodology

The SRS can be updated sprint by sprint in Agile projects, making it a living document. The SRS is generally more formal and locked earlier in the Waterfall.

Either way, it should work seamlessly with the remaining SDLC stages and project documentation.

Review for Readability

At the end, it is important to remember that format is critical. Use tables, bullet points, headings, and standardized fonts. A clear, readable document is used. Cluttered documents are often ignored.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing an SRS

- Vague or subjective requirements: (“System should be user-friendly.” What does that mean?)

- Mixing requirements with design details: The SRS should define outcomes, not implementation.

- Ignoring non-functional requirements: These often cause performance or usability failures later.

- Lack of stakeholder input: An SRS developed in isolation rarely satisfies real needs.

- Not updating the document: Obsolete requirements are worse than missing ones.

- No traceability: When requirements change, teams need to see what’s impacted.

- Over-complication: Long, redundant, jargon-filled SRS documents discourage usage.

A version-controlled, short, and understandable SRS is preferred to a 100-page dense tome that nobody ever picks up.

Integrating the SRS with the Software Design Document

The software design document (SDD) is a logical next step after finishing your SRS.

- What must be constructed is defined by the SRS.

- The SDD specifies the architectures, modules, algorithms, and data models that will be used in its construction.

The two should line up precisely. The SDD and test documentation should also be updated if the SRS changes (for example, a new feature is added).

This connection ensures the consistency and dependability of your whole software documentation ecosystem.

Maintaining the SRS Throughout the Project

- Update the document when new software versions are released or requirements are modified.

- Maintain it in a version-controlled repository that all parties involved can access.

- Document changes in a revision history to ensure accountability.

Maintaining your SRS ensures transparency and long-term maintainability, which is a part of professional project documentation discipline.

A Short SRS Writing Checklist

- Clearly defined objectives and target audience.

- Defined scope and boundaries.

- Stakeholder requirements collected and validated.

- Functional requirements are complete and traceable.

- Non-functional requirements are measurable.

- External interfaces documented.

- Legal and regulatory requirements recorded.

- Glossary and appendices included.

- Reviewed and approved by all parties.

- Version-controlled and baseline established.

Your SRS is developed to lead the project if you can check off each of these points.

Why Every Great Project Starts with a Great SRS

Writing a Software Requirements Specification isn’t just restricted to bureaucracy; it also points to clarity.

It functions as a link between concepts and execution as well as between vision and verification.

- Developers know exactly what to build.

- Testers know exactly what to verify.

- Stakeholders know exactly what to expect.

An SRS keeps your project grounded in reality, regardless of whether you are working for a large organization or a startup. It becomes an effective tool for control, communication, and ongoing development when paired with careful software documentation and an adaptable SRS template. Thus, avoid the urge to avoid the SRS the next time. Give it your best effort. Your team, your end users, and your future self will all appreciate it.

|

|