What are Antipatterns in Software Development?

Software development often balances technical design, coding practices, and problem-solving. Over the years, development professionals have discovered effective ways to solve problems, known as design patterns.

They have also been able to use recurring approaches that seem helpful at first but eventually cause more problems than solutions. These approaches are often harmful to development in the long run.

These approaches are the antipatterns we will be discussing in this article.

| Key Takeaways: |

|---|

|

This article delves into antipatterns in software development, their common types, identification, consequences, and strategies for avoiding them.

What are Antipatterns?

Andrew Koenig, in his 1995 paper “Patterns and Antipatterns,” defined an antipattern as:

An antipattern is just like a pattern, except that instead of a solution, it gives something that looks superficially like a solution but isn’t one.

It is a typical response to a recurring problem that appears useful initially but has long-term negative consequences.

Antipatterns are the opposite of best practices and are a poor solution to a software design or management issue that creates more problems than it resolves. They may even solve the immediate problem, but this is at the cost of performance, scalability, and maintainability.

Hence, unlike design patterns in software development that are formalized and generally considered good development practices, antipatterns are considered flawed.

class GodObject {

function Initialize() {}

function ReadFromFile() {}

function WriteToFile() {}

function PrintToScreen() {}

function Calculate() {}

function ValidateInput() {} // and so on... //

}

class FileInputOutput {

function ReadFromFile() {}

function WriteToFile() {}

}

class UserInputOutput {

function DisplayToScreen() {}

function ValidateInput() {}

}

class Logic {

function PerformInitialization() {}

function PerformCalculation() {}

}

In this code, the functionality is not stuffed into a single object; instead, it is divided into different objects based on the standard functions like FileInputOutput, Logic, and UserInputOutput.

From the above example, we can infer that there are good ways to develop software using design patterns and antipatterns, ultimately leading to problems. The GodObject in the above example may not cause immediate problems, but it will slowly lead to errors and maintenance problems as the code grows.

Key Characteristics of Antipatterns

Here are the key characteristics of antipatterns:

- Recurring Problem: Antipatterns address recurring problems that developers frequently encounter.

- Apparent Solution: The solution that antipatterns offer works initially.

- Negative Consequences: Antipatterns lead to problems in the long run, such as increased complexity, decreased performance, and difficulties in maintaining the software.

- Technical Debt: Antipatterns often generate technical debt, requiring future rework to fix the underlying issues.

Why Do Antipatterns Occur?

Antipatterns often arise in software development due to the following reasons:

- Time Pressure: Developers often face tight deadlines that compel them to choose shortcuts that sacrifice quality for speed.

- Lack of Experience: Junior developers who lack coding experience may resort to practices that seem correct and work without anticipating long-term implications.

- Over-Engineering: Sometimes, mistaking complexity for robustness, developers create complex solutions.

- Organizational Culture: Antipatterns often arise due to poor communication, unclear requirements, or flawed practices.

- Technical Debt: The need to quickly fix errors may accumulate these fixes. Failure to refactor the code may evolve into an antipattern.

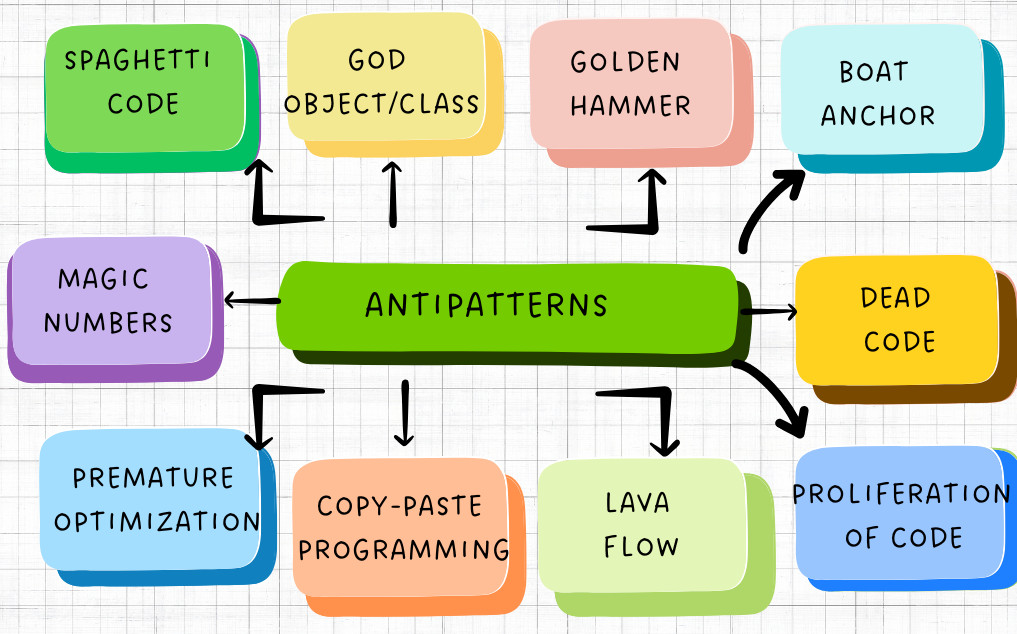

Common Types of Antipatterns in Software Development

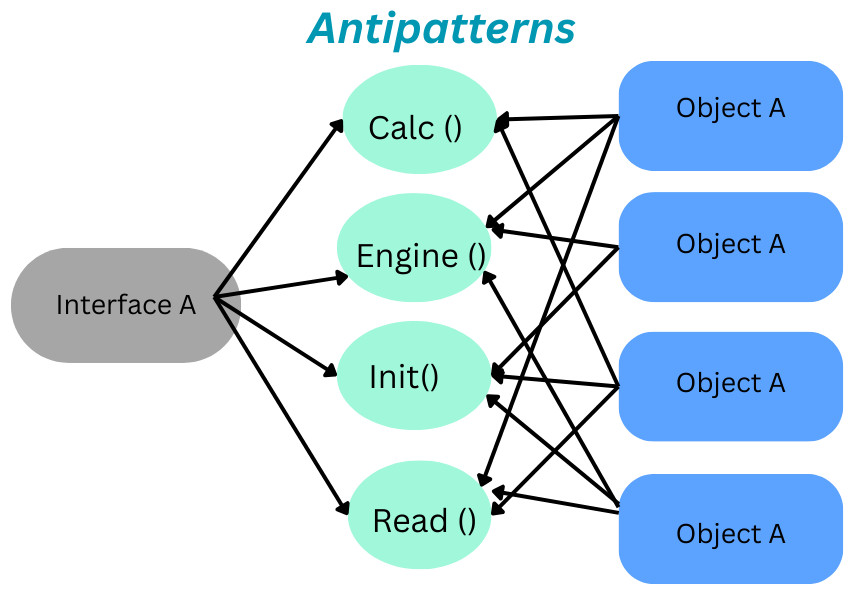

Anti-patterns appear at different levels, such as code, architecture, or even project management. Some of the most common types of antipatterns are explained here:

1. Spaghetti Code

Spaghetti code is the most common antipattern. It is unstructured, tangled code with little to no modularization. Random files are in random directories, and the whole code flow is utterly tangled together (like spaghetti).

Functions and classes are tightly coupled, making changes risky; spaghetti code results from not carefully considering the program’s flow before coding.

Spaghetti code leads to a maintenance nightmare and makes adding new functionality impossible. This code constantly breaks, and developers cannot provide accurate estimates of work as it is impossible to foresee the countless errors that crop up.

2. God Object / God Class

A god object or class does too many things and is everywhere in the codebase. It performs too many responsibilities and handles multiple tasks instead of focusing on one task.

This is also sometimes called the Swiss Army Knife antipattern because developers need it to cut some twine and make code more modular.

Let us understand this antipattern with the following example:

interface Mammals {

numOfLegs: string;

weight: number;

engine: string;

model: string;

sound: string;

claws: boolean;

wingspan: string;

customerId: string;

}

The object that implements this interface will be a god object.

Can you deduce from the above interface declaration that it is doing too many things and needs refactoring? Moreover, the interface has many irrelevant parameters.

interface Mammals {

numOfLegs: string;

weight: number;

sound: string;

claws: boolean;

}

interface Car {

engine: string;

model: string;

}

interface Bird {

wingspan: string;

}

interface Transaction {

customerId: string;

}

In the above code, we have basically segregated the code to make it clearer and more relevant. This way, those who need a bird object will not be forced to implement the Mammals interface.

The god object results from a misunderstanding of object-oriented principles and a fear of having too many small classes.

3. Golden Hammer

The tendency to use a familiar, commonly used tool, framework, or technique for every problem, regardless of whether it fits or is suitable, gives rise to the golden hammer antipattern. In other words, you hammer your way into the code even when the code doesn’t need a hammer but a screw.

If code needs to draw a circle, and you have a ready code to draw a square, you will push the code to draw a square and try to draw a circle.

This happens because you are overconfident in a single technology, framework, or tool and lack exposure to newer alternatives. This leads to performance issues and increased maintenance costs. The golden hammer inhibits innovation and flexibility, leading to suboptimal solutions.

4. Boat Anchor

In the boat anchor antipattern, developers leave code in the codebase for future use.

For example, if a developer codes functionality slightly out of specification and it is not needed yet, he might still store it in the codebase, thinking it will surely be useful next month. Hence, the developer does not delete the code but sends it to production so that when it is needed, it can be used quickly.

This causes serious maintenance problems in the codebase as it contains obsolete code. It is a nightmare for other developers to figure out what code is outdated and doesn’t change the flow, versus the code that works.

Another issue is that obsolete code increases build time, and developers may mix up working and outdated code. It might even be turned on in production.

5. Dead Code

This is similar to a Boat Anchor. A section of code in a file created a few years ago to create some functionality, but is no longer required, gives rise to the dead code antipattern. If you obliterate this code, the software may not crash anywhere, but it can also be dangerous to remove all of the dead code at times.

One example of dead code is code written by someone who no longer works in your company. There is a functionality that doesn’t look like it is doing anything, but it is called from everywhere. Everyone knows it is not doing anything, but nobody dares to delete it.

The dead code antipattern is more common in proof-of-concept (POC) or research code that ended up in production.

6. Proliferation of Code

When there are objects in the codebase that only exist to invoke another more important object, it is a proliferation of code antipattern. This object acts like a middleman, whose only purpose is to call new functions.

Code proliferation adds an unwanted level of abstraction and serves no purpose other than confusing developers who try to understand the codebase’s flow and execution. Simply removing the object and the level of abstraction can fix this issue.

7. Lava Flow

Lava code is code that works but is poorly understood, undocumented, or no longer serves a purpose. It is kept in the system out of fear of breaking something. The main characteristic of lava code is its resistance to change or removal due to a lack of understanding or fear of the consequences.

Examples of lava code are dead code, outdated modules, or temporary fixes that remain in the code repository indefinitely.

The main causes of this antipattern are a lack of proper documentation, poor refactoring discipline, or developers’ fear of removing code.

Such code is difficult to understand and maintain, and it is not possible to know why it is there or why it is needed.

Regular refactoring can reduce the amount of unused code and prevent lava code.

8. Copy-Paste Programming

Junior developers or novice programmers may have difficulty coding some features due to a lack of experience. They might attempt to copy and paste the code from various websites, blogs, videos, or programming platforms like Stack Overflow. They do not conduct research or testing and simply copy and paste the code into their codebase. This gives rise to a copy-paste programming antipattern that behaves like a virus.

This occurs due to a lack of grasp of fundamental concepts like loop structures, functions, and subroutines. As a result, bug fixes must be replicated everywhere, resulting in inconsistent logic across the system.

The maintenance cost of such a codebase is very high. Using the “Don’t Repeat Yourself” (DRY) principle and properly using functions, libraries, and classes can prevent this antipattern.

9. Premature Optimization

When code is optimized for performance before establishing functionality or clarity, it gives rise to premature optimization. This is mainly caused by misplaced priorities and developers’ obsession with speed. This haste results in complex, unreadable code and wasted effort if optimization is not needed at all.

To prevent this antipattern, the principle of making it work first and then making it fast should be adopted. In addition, profiling tools can be used to identify real performance bottlenecks so that the code is not optimized unnecessarily.

10. Magic Numbers

The magic numbers antipattern is a bad programming practice that uses numerical values in the source code without properly naming them.

These magic numbers make the source code less readable and more prone to errors because it is not clear what they represent. Providing a meaningful name or a dedicated explanation for these magic numbers can prevent the occurrence of this antipattern.

Consequences of Ignoring Antipatterns

Some of the consequences of ignoring antipatterns in code are as follows:

- Increased Maintenance Costs: More time is needed to fix issues arising from antipatterns than to build new features. This results in increased maintenance costs.

- Low Developer Productivity: New developers find it hard to understand poor code structures, leading to lower productivity.

- Reduced System Reliability: More bugs and crashes make the system unreliable.

- Scalability Challenges: Antipatterns can cause the system architecture to suffer and prevent its scalability.

- Developer Burnout: Developers have to work with messy code that might reduce their morale and lead to burnout.

How to Identify and Avoid Antipatterns

Here are some ways to identify and avoid antipatterns:

- Code Reviews: Regular reviews should be conducted. Peer reviews often highlight bad practices before they spread throughout the codebase.

- Refactoring: Code should be continuously cleaned up and refactored instead of only being done when problems arise.

- Following Principles: Programming principles such as DRY, Keep It Simple, Stupid (KISS), and SOLID should be followed for systematic coding.

- Continuous Learning: Developers should be knowledgeable about both patterns and antipatterns.

- Automated Tools: To analyse and detect anomalies, static analysis tools, linters, and testing frameworks should be used.

The Difference Between Patterns and Antipatterns

The following table summarizes the key differences between patterns and antipatterns:

| Aspect | Pattern | Antipattern |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Proven, reusable solutions to recurring problems. | Common mistakes that appear useful but harm long-term progress. |

| Impact on code | Improves code quality and maintainability. | Decreases code quality and maintainability. |

| Effectiveness | Proven, effective solution. | Appears effective initially, but problematic in the long run. |

| Intent | To solve a problem elegantly and efficiently. | To solve a problem, but with unintended negative consequences. |

| Context | It works best when applied correctly and in the appropriate context. | It can be detrimental when applied in the wrong context or situation. |

| Example | Singleton, Factory, Observer. | God Object, Spaghetti Code, Lava Flow. |

Conclusion

Antipatterns in software development are more than mistakes; they are recurring traps that attract developers’ attention for short-term convenience while causing long-term problems. It is important to recognize these antipatterns early on to build a sustainable, maintainable, and scalable solution.

By encouraging a culture of clean code, refactoring, peer reviews, and continuous learning, antipatterns can be reduced, and software quality improved. While design patterns solve problems effectively, antipatterns represent the dangers of taking shortcuts or misapplying programming solutions.

Avoiding antipatterns is about creating software that can evolve, scale, and serve users effectively for a long time.

Additional Resources

- Four Types of Software Maintenance: A Detailed Guide

- What is Code Optimization?

- What are the Different Types of Code Smells?

- Cohesion vs Coupling

- What is Software Architecture?

|

|